Celebrating 350 years of Jewish Life in Brandenburg

The framework conditions of Jewish life from 1671 onwards

On the website celebrating 350 years of Jews in Brandenburg, the following was said about the year of commemoration 1

„On 21 May 1671, the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm issued an edict for the settlement of 50 Jewish families expelled from Vienna. The resettlement of Jews represents a turning point in their history in Brandenburg. From then on, Jewish life developed continuously in the state and many communities traced their origins back to this year“.

All in all, this sounds like a normal historical process tor those who are not familiar with Jewish history in Brandenburg.

However, this is not the case. For most of the 350 years, Jewish lives differed significantly from those of the non-Jewish poplation of Brandenburg:

- In the first 200 years following their resettlement, Jews had fewer rights than Christians.

- After that, they were equals – in the eye of the law – for about 60 years,

- Then, under the National Socialists, they were again disenfranchised, expelled and finally murdered in large numbers until the end of the Second World War.

It was not until after the reunification of Germany that a few new Jewish communities were founded on the territory of the Federal State of Brandenburg.

Historians who have been dealing with the last 350 years of Jewish history in Brandenburg believe that many historical events are significant and worthy of further explanation.

The text that follows focuses on a few events and time periods which were especially significant in defining the professional and private framework of Jewish life in the region.

From 1671 The resettlement of Jews is made possible

In 1571, Elector Joachim II died unexpectedly on a hunting trip. His death was blamed on the Court Jew Lippold, who was accused of having poisoned the Elector 2. Shortly after the Elector’s death, all Jews living in Frankfurt/Oder were ordered by Elector Johann Georg, Elector Joachim II´s successor, to leave the Mark Brandenburg 3. All other Jews – except those converting to Christianity – were expelled from the Electorate in the years that followed 4 5.

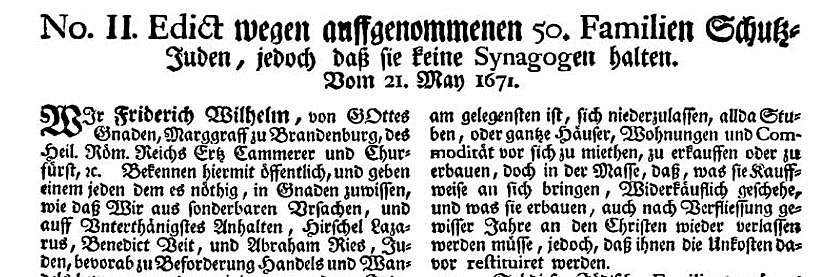

It would take 100 years before Jews would be allowed to settle in the Mark Brandenburg again. With the edict of 21 May 1671 (Fig. 1) the “Great Elector” Friedrich Wilhelm allowed 50 wealthy Jewish families who had been expelled from Austria the year before to settle in the Electorate for 20 years 6.

Fig. 1: Edict of 21 May 1671 (Extract)

The Elector’s 1671 settlement permission was motivated by the hope that Jewish families would bring economic benefits to the region given their business experience and connections 7.

The Jews who entered from Austria had to pay protection money in order to obtain the right to live in Brandenburg. A letter of protection issued after the payment of the protection money specified where they were allowed to live and what form of trade they were permitted to perform. The new settlers were only allowed to practice their religion to a limited extent 8.

A large number of the newcomers settled in Berlin where the sovereign ruler resided and in Frankfurt an der Oder, known for its trade fair. Jewish settlers were also reported in Beelitz, Brandenburg an der Havel, Freienwalde, Friesack, Landsberg an der Warthe, Nauen and Wriezen in the years that followed 9.

From 1700 Jewish life is greatly confined

In the first half of the 18th century, the rules under which Jews could live in Brandenburg were revised several times 10.

In this context, the General Jewry Regulations (1730) 11 and the Revised General Privilege (1750) 12, which remained valid until 1812, are particularly worth mentioning 13.

With the help of an extensive set of regulations, the Prussian kings Frederick William I and his successor Frederick II attempted to limit the number of Jews living in the country while simultaneously seeking to maximize the amount of economic benefit to be reaped from them 14.

The General Jewry Regulations (1730)

The General Jewry Regulations of King Frederick William I, dating from 1730, are deemed “the first (..) Jewry regulations with a nationwide claim” 15.

The text of the law (28 paragraphs)

- considerably restricted the economic activity of Jews through a large number of prohibitions (§2 – §7, §9),

- limited the purchase of houses to those holding a special permission (§8),

- limited the number of Jewish families living in Berlin to 100 and stipulated that the number of protected Jews (“Schutzjuden”) living outside Berlin should remain constant (§10). However, very wealthy Jews were offered the prospect of resettlement (§16).

The General Jewry Regulations had serious consequences for the private lives of Jewish families, because it held that a protected Jew could only pass on the right of settlement and marriage to the first and second son if they were able to prove sufficient assets 16.

The Revised General Privilege (1750)

The Revised General Privilege of 1750 issued by King Frederick II was even more extensive than the General Jewry Regulations. In the introduction to the text of the law, the king stated that the following would be stopped in order to protect Christian merchants, the inhabitants, but also the Jewish community. 17.:

- the “rampant multiplication” of “protected and tolerated Jews” in his kingdom, as well as

- the “creeping in of non-protected Jews, strangers as well as Jews who were almost not at home anywhere”

At the same time, the king emphasised that the welfare of all his subjects, both Christians and Jews, was important to him.

How he wanted to prevent the increase of the legitimately resident Jewish population became clear in Sections III and V of the Revised General Privilege, which laid down rules for different parts of the Jewish population.

In Section III, the legislator prescribed how many public servants the Jewish community in Berlin and Jewish communities elsewhere were allowed to have.

Particularly serious for the future of Jews residing within the scope of the law was Section V, which newly regulated their right to remain in the country and made this even more restrictive than in the General Privilege of 1730 18.

The Revised General Privilege made it clear in its concrete design and implementation that poor and non-wealthy Jews were not welcome in the country.

From 1812 Jews are allowed to acquire Prussian citizenship

Fundamental changes in the legal situation of the Jewish population did not occur until long after the death of King Frederick II and his successor King Frederick William II in the 19th century 19.

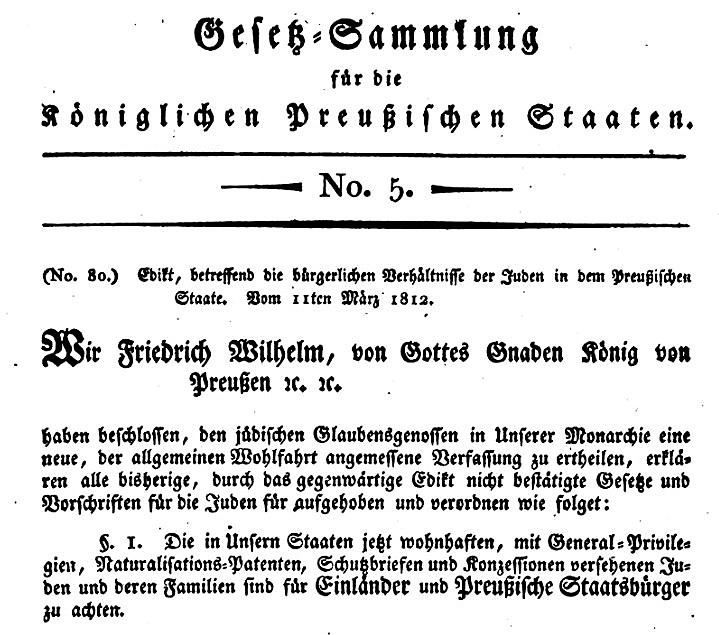

The much longed for lifting of restrictions relating to the private and professional lives of Jews, including special financial burdens finally came, if only in part, with an edict issued by King Frederick William III on 11 March 1812 (Fig. 2) 20.

Fig. 2: Edict issued on 11 March 1812 (Extract)

The law only applied to Brandenburg and four other Prussian provinces: Pomerania, West Prussia, East Prussia and Silesia 21. The Prussian province of Posen, where a great many Jews lived at the time, was excluded.

With the edict, Jews living in the five provinces, insofar as they belonged to the group of privileged Jews, largely enjoyed the same rights as the Christian residents 22.

Jews who wanted to become Prussian citizens had to fulfil an important condition in advance:

they had to inform the authorities of their place of residence within 6 months of the publication of the edict and also state which family name they would use in future (§ 3).

For the first time, the edict gave Jews the possibility of deciding where they wanted to reside (§ 10). They were also allowed to acquire real estate and to carry out all trades (§ 11, § 12). Furthermore, domestic Jews were assured that they would no longer be burdened with special taxes (§ 14)..

However, the promised free choice of occupation was already restricted again between 1820 and 1835 by individual decrees 23.

There is also a remarkable document from a genealogist’s point of view, which was published in October 1814 24: a list with the names of a total of 2700 Jews living in the Kurmark who had received citizenship letters on the basis of the Edict of 1812.

The list contained, sorted by place of residence, both the old and the new names of the new Prussian citizens, as well as partial information on their family status and occupation.

From 1869 Full legal equality of Jews and Christians

In 1869, the Jewish population achieved full legal equality for the first time in Brandenburg and other parts of Prussia.

In the “Law Concerning the Equal Rights of Confessions in Civil and Civic Relations”, Wilhelm I, King of Prussia, in the name of the North German Confederation, declared that

- “All remaining restrictions on civil and civic rights derived from differences of religious confession” would be abolished 25.

The law expressly granted Jews the right to hold public office 26.

From 1933 Disenfranchisement, emigration and systematic extermination

The overall positive trend in the general conditions of Jewish life in Brandenburg came to an abrupt end when the National Socialists came to power on 30 January 1933. Within a few years, Jewish citizens were completely deprived of their rights 27.

Many of them left Brandenburg during these years: they moved to Berlin or emigrated directly 28. The move to Berlin was linked to the hope that the anonymity of the big city would offer a certain level of protection.

No information is available on the number of Brandenburg Jews who left Germany from 1933 onwards. Even the total number of emigrated Jews is disputed 29.

Legal emigration came to an end on 18 October 1941 with an order by Heinrich Himmler to prevent the departure of Jews with immediate effect 30. This was the starting point for the systematic extermination of the Jewish population 31.

Brandenburg Jews were subsequently deported to concentration and mass extermination camps until the beginning of 1945 32 33.

Jewish communities that had grown over centuries were almost completely wiped out by the end of the war.

From 1991 Rebuilding Jewish communities and commemorating the past

After the end of the war, not a single Jewish community existed in what is now the Federal State of Brandenburg 34.

This was only to change after the reunification of Germany, when numerous Jews from Russia and other successor states of the Soviet Union came to Brandenburg, some of whom settled there from 1991 onwards 35.

The newcomers had a completely different cultural and religious background than those Jews who had lived in Brandenburg before their expulsion and the Holocaust. They had been “socialised communist-atheist” in the Soviet Union and only very few of them were familiar with “religion and customs” 36.

As early as 1991, the first Potsdam congregation came into being, whose founding members were almost exclusively from the former Soviet Union. By 2000, new congregations had been established in Brandenburg/Havel, Bernau, Cottbus, Frankfurt (Oder) and Königs Wusterhausen 37.

All Brandenburg communities together are estimated to have about 2000 members today 38, belonging to different streams of Judaism 39.

Parallel to the revival of Jewish life, both the centralised and decentralised commemoration of the National Socialists’ reign of terror began in the first half of the 1990s.

- Since then, with the help of local initiatives, so-called Stolpersteine (stumbling stones) have been laid all over Brandenburg as a reminder of the crimes committed during the Third Reich 40.

- In addition, the Brandenburg Memorials Foundation was established, which also includes the Sachenhausen and Ravensbrück concentration camps. Its main role is described as follows: “The foundation’s task is to commemorate terror, war and tyranny and to promote public discussion of these topics” 41.

Footnotes

1 350 Jahre Juden in Brandenburg, Willkommen, online: https://juden-in-brandenburg.de/, (last accessed on 14.2.2022)

2 For a detailed account of the life of Lippold, the Court Jew, and especially of the years between his arrest (1571) and his execution (1573), see: WOLBE, Eugen: Geschichte der Juden in Berlin und in der Mark Brandenburg, Berlin 1937, pages 74 – 88

3 WOLBE, Eugen, page 85 f

4 The expelled Jews mainly settled in Prague, but also in Poland. WOLBE, Eugen, page 86 f

5 DAVIDSOHN, Ludwig: Beiträge zur Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte der Berliner Juden von der Emanzipation, Berlin 1920, page 16

6 DIEKMANN, Irene A.: Juden in Brandenburg (1671 bis 1871), in: Historisches Lexikon Brandenburgs, online: https://brandenburgikon.net/index.php/de/sachlexikon/juden-in-brandenburg-1671-bis-1871, (last accessed on 14.2.2022)

7 KÖHLER, Benjamin: Jüdische Akteure in Brandenburg-Preußen, Kapitel 3: Einwanderungspolitik von 1671 bis 1713: Wandel durch Handel, online: https://germanjews.hypotheses.org/36, (last accessed on 14.2.2022)

8 DIEKMANN, Irene A.: Juden in Brandenburg (1671 bis 1871)

9 DIEKMANN, Irene A.: Juden in Brandenburg (1671 bis 1871); see also: NEUMANN, Emanuel: Jüdisches Leben in Brandenburg, in: Stolpersteine Brandenburg, online: https://www.stolpersteine-brandenburg.de/de/hintergrund/juedisches_leben_in_brandenburg.html, (last accessed on 14.2.2022); see also LASSALLY, Oswald: “Zur Geschichte Der Juden in Landsberg a.d. Warthe.” Monatsschrift Für Geschichte Und Wissenschaft Des Judentums, Vol. 80 (N. F. 44), No. 5, 1936, pages 403 – 415, online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23113420, (last accessed on 7.3.2022 )

10 BREUER, Mordechai: Die jüdische Minorität im Staat des aufgeklärten Absolutismus, in: BREUER, Mordechai, GRAETZ, Michael (Hrsg.): Deutsch-jüdische Geschichte in der Neuzeit, Band I, 1600 – 1780, München 1996, pages142 – 144; vgl. DIEKMANN, Irene A: Juden in Brandenburg (1671 bis 1871)

11 Corpus Constitutionum Marchicarum (CCM), Fünffte Abtheilung. Von unterschiedenen zum Policey-Wesen gehörigen Sachen, Das III. Capitel. Von Juden-Sachen, Nr. LIII, General-Privilegium und Reglement, wie es wegen der Juden in Sr. Königl. Majestät Landen zu halten, De Dato Berlin, den 29.September 1730

12 Novum Corpus Constitutionum Prussico-Brandenburgensium Praecipue Marchicarum (NCC), Band 2, 1756,. Nr.65, Cabinetsordre wegen des General-Juden-Reglements, wobey befindlich: Revidirtes General-Privilegium und Reglement, vor die Judenschaft im Königreiche Preussen, der Chur- und Mark-Brandenburg, den Herzogthümern und Fürstenthümern, Magdeburg, Cleve, Hinter-Pommern, Crossen, Halberstadt, Minden, Camin und Meurs; imgleichen den Graf und Herrschaften, Mark, Ravensberg, Hohenstein, Tecklenburg, Lingen, Lauenburg und Bütow vom 17ten April 1750.

13 Schoeps, Julius H.: Der lange Weg zum Staatsbürger, in: Jüdische Allgemeine vom 6.3.2012, online: https://www.juedische-allgemeine.de/kultur/der-lange-weg-zum-staatsbuerger/, (last accessed on 16.3.2022 )

14 BREUER, Mordechai, pages 141 ff

15 SCHENK, Tobias: Das Emanzipationsedikt – Ausdruck „defensiver Modernisierung“ oder Abschluss rechtsstaatlicher Entwicklungen des „(aufgeklärten) Absolutismus“? 1812 – 1912 – 2012. Versuch einer Standortbestimmung, in: DIEKMANN, Irene A. (Hrsg.), Das Emanzipationsedikt von 1812 in Preußen, Der lange Weg der Juden zu „Einländern“ und „preußischen Staatsbürgern“, Berlin, Boston 2013, page 47

16 SCHENK, Tobias: Das Emanzipationsedikt, page 53

17 Jews who had a letter of protection granting them special rights, were called “Vergleitete” Jews. “Unvergleitete” Jews, on the other hand, had no letters of protection and were at best tolerated in the country.

18 SCHENK, Tobias: Das Emanzipationsedikt, pages 55 ff

19 Regarding the policies towards the Jews during King Friedrich Wilhelm II ´s reign, see: JERSCH-WENZEL, Steffi: Rechtslage und Emanzipation, in: BRENNER, Michael, JERSCH-WENZEL, Steffi, MEYER, Michael A. (Hrsg.): Deutsch-jüdische Geschichte in der Neuzeit, Band 2, 1780 – 1871, München 1996, pages 26 – 32

20 Gesetzsammlung für die Königlichen Preußischen Staaten, No.5, Nr.80: Edikt betreffend die bürgerlichen Verhältnisse der Juden in dem Preußischen Staate. Vom 11ten März 1812

21 DIEKMANN, Irene A.: „bevorab zu Beförderung Handels und Wandels“: 350 Jahre Wiederansiedlung der Juden in Brandenburg. Hauptlinien ihrer Entwicklung von 1671 bis 1945, online: https://juden-in-brandenburg.de/350-jahre-wiederansiedlung-der-juden-in-brandenburg/, (last accessed on 29.3.2022)

22 Almost 90 % of all Jews residing in Prussia fulfilled this requirement at this time. see: DIEKMANN, Irene A.: „bevorab zu Beförderung Handels und Wandels“

23 DIEKMANN, Irene A.: „bevorab zu Beförderung Handels und Wandels“ (last accessed on 29.3.2022)

24 Beilage zum 40sten Stück des Amtsblatts der Königl. Kurmärkischen Regierung, Potsdam 1814

25 Gesetz, betreffend die Gleichberechtigung der Konfessionen in bürgerlicher und staatsbürgerlicher Beziehung. Vom 3. Juli 1869 (Bundesgesetzbl. S. 292)

26 Gesetz, betreffend die Gleichberechtigung der Konfessionen in bürgerlicher und staatsbürgerlicher Beziehung. Vom 3. Juli 1869.

27 On the chronological development of the persecution of the Jews from 1933 onwards, see: Zeittafel der Judenverfolgung 1933 – 1945, online: https://www.archiv.sachsen.de/download/Strukturen_der_Macht_Zeittafel.pdf., (last accessed on 16.3.2022

28 NEUMANN, Emanuel (last accessed on 8.3.2022)

29 BERGMANN, Armin: Die sozialen und ökonomischen Bedingungen der jüdischen Emigration aus Berlin/Brandenburg 1933, Dissertation Berlin 2009, pages 56 ff, online: https://depositonce.tu-berlin.de/bitstream/11303/2425/2/Dokument_48.pdf, (last accessed on 8.3.2022)

30 bpp, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: Vor 75 Jahren: Ausreiseverbot für Juden, online: https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/hintergrund-aktuell/235829/vor-75-jahren-ausreiseverbot-fuer-juden/, (last accessed on 11.3.2022)

31 During that time, approx. 163,000 people of Jewish faith still lived in the German Reich. see: bpp, Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung: Vor 75 Jahren.

32 NEUMANN, Emanuel (last accessed on 8.3.2022)

33 Statistik und Deportation der jüdischen Bevölkerung aus dem deutschen Reich, Bezirksstelle Brandenburg-Ostpreußen, online: https://www.statistik-des-holocaust.de/list_ger_brb.html, (last accessed on 8.3.2022)

34 WEISSLEDER, Wolfgang: Der Neuaufbau jüdischer Gemeinden in Brandenburg ab 1991 – die ersten 10 Jahre, in: DIEKMANN, Irene A. (Hrsg.): Jüdisches Brandenburg, Geschichte und Gegenwart, Berlin 2008, page 290

35 It is estimated that 7500 Jews from the Soviet Union and its successor states were accepted in Brandenburg, many of whom later moved to Berlin and other federal states. WEISSLEDER, Wolfgang, page 330

36 WEISSLEDER, Wolfgang, page 329

37 Chronologie zur Geschichte der Juden in Brandenburg von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart, in: DIEKMANN, Irene A. (Hrsg.): Jüdisches Brandenburg, Geschichte und Gegenwart, Berlin 2008, page 648

38 GLÖCKNER, Olaf, Jüdisches Leben in Brandenburg heute, Einführung, online: https://juden-in-brandenburg.de/einfuehrung-juedisches-leben-in-brandenburg-heute/, (last accessed on 17.3.2022)

39 In Potsdam, for example, there have long been three different Orthodox Communities (the “Law-abiding”, the Jewish Community and the Synagogue Community) as well as the “Beth Hillel”, which belongs to liberal Judaism. RÖD, Ildiko: Juden gegen die “Kirche der Schande”, in: Märkische Allgemeine vom 2.7.2014, online: https://www.maz-online.de/Thema/Specials/G/Garnisonkirche-in-Potsdam/Juden-gegen-die-Kirche-der-Schande, (last accessed on 14.3.2022). Furthermore, the liberal community “Kehilat Israel”, founded in 2020 for Israelis living in the state of Brandenburg. RICHTER, Christoph: Jüdische Gemeinde für Israelis in Potsdam /„Du musst Dich selber schützen“, in: Deutschlandfunk vom 11.6.2021, online: https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/juedische-gemeinde-fuer-israelis-in-potsdam-du-musst-dich-100.html, (last accessed on 14.3.2022)

40 Stolpersteine Brandenburg, Tagung: Dezentrales Gedenken. Stolpersteine, lokale Geschichtsprojekte und digitales Erinnern, online: https://www.stolpersteine-brandenburg.de/, (last accessed on 8.3.2022)

41 Stiftung Brandenburgische Gedenkstätten, Aufgaben, online: https://www.stiftung-bg.de/die-stiftung/aufgaben/, (last accessed on 8.3.2022)

Author

Klaus Boas (Research Group “Jews in Brandenburg”)